(PRESS STATEMENT)

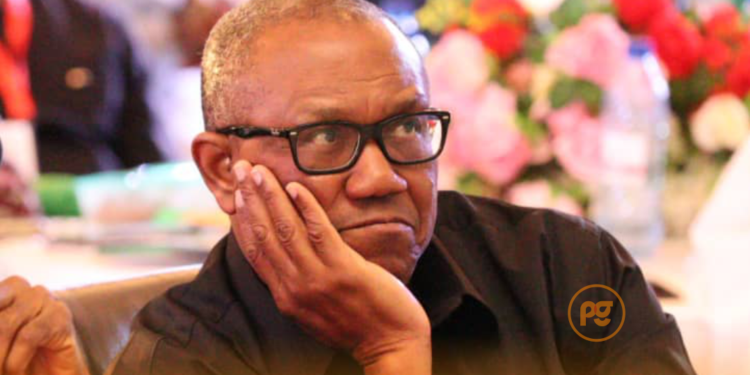

The final legal battle for the contentious February 25th, 2023 Presidential Election begins with the Labour Party Presidential Candidate, Peter Gregory Obi, and the Labour Party, filing an appeal against the September 6, 2023 ruling of the Presidential Election Petition Court, PEPC.

Obi and LP’s team of lawyers led by Dr Livy Uzokwu SAN today, September 19, 2023, complied with the statutory deadline for the filing of the Appeal and approached the apex court on 51 grounds, which they termed an error in law to prove that the All Progressives Congress, APC Presidential Candidate in the election, Bola Ahmed Tinubu did not win the election and that it was wrong for both INEC and the PEPC to declare him winner of the election when many incontrovertible points were proving otherwise.

In enunciation their grounds, Obi and the Labour Party sought from the apex Court, four key points; Allow the Appeal, set aside the perverse judgement of the PEPC, and grant the Reliefs sought in the petition, either in the main or in the alternative.

On the issue of the 25% requirement for Abuja, Obi and the Labour Party listed the particulars of error by the PEPC as follows. That the PEPC failed to appreciate that for the President to assume the office or position of the Governor of Abuja, is also under a mandate to secure 25% of the votes cast in the FCT.

They also accused the PEPC of overlooking the fuller purport of section 299 which will be more glaring on a calm examination of section 301 of the constitution.

No date yet has been fixed for the hearing of the case.

E-Signed

Obiora Ifo

National Publicity Secretary.

Labour Party

THIS IS THE SUMMARY OF THE GROUNDS OF APPEAL IN PETER OBI’S APPEAL TO THE SUPREME COURT

Although the appeal filed by Peter Obi and the Labour Party to the Supreme Court against the Judgment of the Presidential Election Petition Court (PEPC) is based on fifty-one (51) grounds of appeal, the major complaints they raised against the Judgment are as follows; that:

The PEPC was wrong when it struck out the witness statements on oath of ten (10) out of the thirteen (13) witnesses called by the Petitioners on the ground that the statements were filed after the expiration of the period of twenty-one (21) days prescribed by the 1999 Constitution (as amended) for them to file the statements. They complain that the decisions of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal which the PEPC cited in support of the decision do not apply to the facts of this case. That the Court of Appeal, in coming to the above decision, refused to follow its previous decisions in many cases, which were cited and submitted to it, that a subpoenaed witness need not file his statement alongside the petition and any such statement filed after the time allowed for filing the Petition is competent and valid. (See Grounds 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 of the Notice of Appeal).

The PEPC was also wrong when it struck out the witness statements on oath of the Petitioners’ witnesses (i.e. PW4, PW7, and PW8 who were Expert Witnesses) on the ground that they were persons interested in the outcome of the Petition. They failed to consider and appreciate the decisions of the Supreme Court to the effect that a person interested means “a person who has a pecuniary or other material interest in the result of the proceedings – a person whose interest is affected by the result of the proceedings, and therefore, would have a temptation to pervert the truth to serve his personal or private ends”. The PEPC failed to take into account that in this case, there is no evidence on record in the instant case that any of the Petitioners’ witnesses had any pecuniary or material interest in the result of the proceedings.

It is also their complaint here that by the decisions of the Supreme Court, a person interested does not mean “an interest in the sense of intellectual observation or an interest purely to the same party. It means an interest in the legal sense which imports something to be gained or lost”. That the interest of PW4, PW7, and PW8 in relation to the documentary evidence produced by them, on subpoena, was merely products of intellectual exercise. The PEPC ought not to have struck out their evidence on this ground. (See Ground 15 of the Notice of Appeal)

The PEPC was wrong when it decided that the electronic transmission of results with the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) from the polling units to the IReV is not mandatory under the provisions of the Electoral Act, 2022; and that INEC has a discretion whether or not to use BVAS to upload and transmit the results. In coming to this conclusion, the PEPC relied on the decision of the Federal High Court in Suit No: FHC/ABJ/CS/1454/2022 and refused and ignored the recent decision of the Supreme Court in OYETOLA v. INEC (2023) LPELR-60392 (SC) that the use of BVAs to scan and transmit the results of the election from the polling units to the IReV is “part of the election process” under the new legal regime governed by the Electoral Act, 2022. The PEPC also ignored the decision of the Supreme Court in OYETOLA’s case that “the Regulations provide for the BVAS to be used to scan the complete result in Form EC8A and transmit or upload the scanned copy of the polling unit result to the Collation System and INEC Result Viewing Portal (IReV)….”

It is their further complaint that contrary to the decision of the PEPC, the use of BVAS to transmit the election results to IReV under the present legal regime governed by the Electoral Act 2022 is mandatory. They contend in coming to the above decision, the PEPC overlooked the provisions of Paragraph 2.9.0 on page 36 of the Manual for Election Officials, wherein INEC stated the mischief the introduction of electronic transmission of results was meant to remedy under the new Electoral Act 2022 under the sub-heading “Electronic transmission/upload of the election result and publishing to INEC Result Viewing (IREV) Portal”, wherein INEC explained that:

“One of the problems noticed in the electoral process is the irregularities that take place between the Polling Units (PUS) after the announcement of results and the point of result collation. Sometimes results are hijacked, exchanged, or even destroyed at the PU, or on the way to the Collation Centers.”

The PEPC also failed to consider that in the same Manual and Guidelines, INEC stated that: “it becomes necessary to apply technology to transmit the data from the Polling Units such that the results are collated up to the point of result declaration. The real-time publishing of polling unit-level results on the IREV Portal and transmission of results using the BVAS demonstrates INEC’s commitment to transparency in results management.”

They further complain that since INEC itself had stated in the same paragraph 2.9.0 of the Manual for Election Officials that this commitment is backed by Sections 47(2), 60(1, 2 & 5), 64(4)(a & b) and 64(5) of the Electoral Act 2022, the PEPC was wrong when it held that the provisions of the Manual on electronic transmission of results conflict with the Electoral Act. They make the case that since the provisions of the Manual complement the provisions of the Electoral Act 2022 in this respect, there is no conflict between the provisions of the Electoral Act and the Guidelines and Regulations; and the issue of the Electoral Act superseding or prevailing over the Guidelines does not arise in the circumstance. (See Grounds 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 29, 30, 31, and 32 of the Notice of Appeal)

The PEPC was wrong when it refused to hold that since INEC had represented and assured the whole world in the exhibits and video recordings tendered by the Petitioners in Court that it [INEC] was going to use the BVAS to transmit the results of the election from the polling units to the IReV electronically as mandated by the Electoral Act 2022, INEC could not turn around in this case to now argue that it had discretion on whether to use the BVAS or not.

The decision of the PEPC makes a complete “nonsense” of the chief objectives of the provisions of the Electoral Act 2022. Contrary to the decision of the PEPC, “it is clear from the pleadings and evidence adduced that the failure of the 1st Respondent to upload and transmit the results of the elections from the polling unit to IReV as mandated by law substantially affected the outcome of the election, in that the credibility, integrity, and transparency of the entire election process were compromised and could not be guaranteed.” (Grounds 25 and 28 of the Notice of Appeal)

The PEPC was wrong when it declined jurisdiction to determine the issue of disqualification of the 2nd Respondent (Tinubu) based on the alleged double-nomination of his Vice-President. The PEPC ignored and refused to follow its previous decisions wherein it had relied on extant decisions of the Supreme Court and emphatically held that the issue of double-nomination as raised by the Appellants herein is an issue of qualification that can comfortably be brought and ventilated under 138(1)(a) of the Electoral Act 2010 (as amended), now Section 134(1)(a) of the Electoral Act, 2022.

The PEPC was wrong when it concluded that the Petitioners did not prove their case of double-nomination of the Vice-President (Kashim Shettima) because the law and evidence tendered in the Court did not support that conclusion. (See Grounds 33, 34 and 35 of the Notice of Appeal)

The PEPC misapplied the provisions of Section 137(1)(d) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) when it reasoned and concluded that the 2nd Respondent (Tinubu) was not disqualified from contesting the Presidential Election based on the forfeiture orders made against him by the US District Court. The PEPC wrongly read the provisions of Section 137(1)(e) of the Constitution (which is a different and independent provision) together with Section 137(1)(d) of the Constitution and concluded that there is no evidence that the 2nd Respondent had been arrested, charged and convicted by a Court of Law to warrant his disqualification from contesting the election.

They complain that the interpretation given by the PEPC is contrary to settled principles of interpretation and the abundant binding case law cited and commended to it on the meanings of “fine” and “forfeiture”. The Court below failed to give a broad, liberal, and purposive interpretation to Section 137(1)(d) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) as laid down and enjoined by the Supreme Court in cases too numerous to mention. (See Grounds 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, and 44 of the Notice of Appeal)

The PEPC was wrong when it decided that a winner of the Presidential Election does not need to score at least 25% of the votes cast in the FCT, Abuja, under Section 134(2)(b) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended). It is complained that the PEPC ought not to have relied on the Preamble to the Constitution to interpret the provision because the provision is clear and unambiguous. The law is that the Preamble in an enactment (including the Constitution) can only be resorted to in order to “clarify any ambiguity in the words used in the enacting part”; and it “cannot be used to give a different meaning to the clear wording of a provision.” They also contended that the PEPC introduced and relied on extraneous matters/considerations in its interpretation of Section 134(2) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) because the issue before the Court was not whether or not the FCT has a “special status” over other States; or whether or not every citizen of Nigeria has the equality of vote; or whether or not the right of every such citizen to elect their President whose policies are supposed to and will affect all of them equally regardless of which part of the country they reside or live” as erroneously invented by the Court below. (See Grounds 45, 46, 47, 48, and 49 of the Notice of Appeal)